We began by considering a bust of world heavyweight boxing champion Joseph Louis Barrow (better known as Joe Louis, 1914-1981) and my assertion that his history might reveal much about changing race relations in the United States. Both of Louis’s biological parents were children of former slaves, and his family had worked as sharecroppers in the South until (like more than a million other African Americans) they migrated North after the First World War to escape KKK terror and poverty. But it was in the boxing ring that Louis made his own important contribution to the fight against racism. Although he had lost a 1936 match to the German prize fighter, Max Schmeling—(which the Nazis touted as proof of Aryan racial superiority)—a second bout had been arranged for the summer of 1938. Just weeks before the scheduled rematch, Louis visited the White House where President Roosevelt encouraged him to use his muscles to demonstrate to the world that the fallacy of the Nazi “superman” myth. Louis did not disappoint. The fight in Yankee Stadium was broadcast live by radio around the globe, and caused a sensation when Louis knocked Schmeling to the mat three times within the first two minutes of the match, with Schmeling’s trainer throwing in the towel on the third fall. Louis’s victory, (coupled with African American runner Jesse Owen’s earlier successes at the 1936 Olympic games held in Berlin), helped persuade Americans to reject the racist doctrines espoused by Nazi propagandists. Little more than a month after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Louis enlisted in the army and afterwards allowed his image to be used to encourage other African Americans to do likewise, and when reporters questioned him about his decision to enlist into the racially-segregated armed services, he replied that there were “Lots of things wrong with America, but Hitler ain’t going to fix them.” Although this next poster is not one from our collection, I could not resist including it here as a perfect example of how Joe Louis's fame and image was used to persuade other Americans to join the fight.

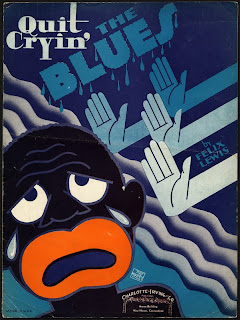

After contemplating Louis’s statue staring out from behind the glass walls of the library stacks, the students entered the library main reading room to look at a wide variety of books, periodicals, and other printed paper materials documenting the experiences of African Americans in the united States. The groups talked about Jim Crow laws and segregation; the promises for better treatment held out to African American men who served their country with pride in the First World War, and the disappointing reality that awaited Black veterans returning home from military service. We talked about lynchings and looked at examples of racial stereotyping from the twenties and thirties.

We also talked of the Great Migration of African Americans (like Joe Louis’s family) to Northern cities in the 1920s and 1930s; the crippling effects of the Great Depression made worse by racism; the trials and tribulations of the nine “Scottsboro Boys” who barely escaped lynching only to endure years in prison during a slew of trials, appeals, mistrials, and retrials in a legal campaign organized by the Communist Party of the United States of America; the Roosevelt Administration’s efforts to provide some measure of economic security and parity for unemployed African Americans within the federal relief programs.

Finally, we wrapped up by coming full circle back to Joe Louis and other African Americans who were encouraged to participate in helping Uncle Sam win the Second World War, cognizant that there was still much to be done for civil rights in America, but only after the threat of the Nazis’ New Order was eradicated.

No comments:

Post a Comment