In commemoration of the Veterans Day holiday, I thought I would put down a few thoughts regarding the treatment of those men (and women) that have served, fought, suffered, and often died for this country since its inception in 1776. The holiday grew out of President Woodrow Wilson’s proclamation of Armistice Day, November 11, 1919 at the end of the First World War; a Congressional resolution in 1926 calling for appropriate ceremonies; and final approval in 1938 of a legal holiday “dedicated to the cause of world peace.” In 1954, Armistice Day was changed to Veterans Day to include honoring the services of veterans of all the war fought by the soldiers of the United States.

But the treatment of America’s veterans has a far longer and tumultuous tradition than the history of the holiday might imply. In fact, one of the very first rebellions faced by the newly-formed American Republic, (Shays Rebellion), took its name from the former Revolutionary war veteran who led a band of discontented veterans to demand a redress of their grievances. Many revolutionary war soldiers had been conscripted, fought without pay, and had been shabbily-treated upon discharge, including being locked up in debtor’s prison. In response to high taxes, confiscations, and foreclosures of their family farms, more than a thousand former soldiers banded together in 1786-1787, occupying county courthouses in Western Massachusetts to forestall property seizures. When their petitions to the Massachusetts governor were ignored and their leaders threatened with “treason,” the veterans attempted to seize the federal arsenal at Springfield, but were routed with some casualties, and their militia soon after disbanded and their leaders slipped away or were arrested.

Sadly, World War I veterans, for whom the holiday originated, were not so better treated in the height of the Great Depression. When in 1932 a bill was introduced into Congress that would have provided immediate (and desperately-needed) compensation to veterans for lost wages during their time of service, some veterans organized a Bonus Expeditionary force to march on Washington and put pressure on Congress to pass the bill. Ultimately, 43,000 desperate veterans and their families converged on the capital, setting up a large “shantytown” on the Anacostia flats on the city’s outskirts. While the bill passed the House, it was killed by the Senate, and President Hoover authorized the army under General MacArthur to drive the lingering protesters out with tanks, teargas, and bayonet point. The burning of the camps by the army did not help Hoover’s re-election campaign!

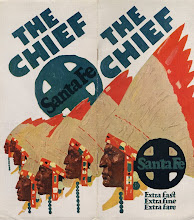

These last two images come from two recent donations to the Wolfsonian-FIU library. The first is an illustration of a disabled WWI veteran reduced to selling pencils and begging for aid. It was designed as Communist Party propaganda by Hugo Gellert during the Great Depression. The second is the dust jacket of a book documenting the “Bonus March” and its unhappy ending.

On a brighter note, in 1944 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act (popularly known as the G.I. Bill) into law, guaranteeing veterans assistance in returning to civilian life. The law provided for vocational training or college education, unemployment compensation, and even federal-subsidized loans for home mortgages or starting up new businesses.

No comments:

Post a Comment