This morning we had an early morning visit to the library by the French Ambassador to the United States Pierre Vimont, the French Foreign Trade Minister Anne-Marie Idrac, the Consul General of France at Miami Gaël de Maisonneuve, and others here in Miami to attend an important economic conference. In preparation for their visit, I had pulled a representative sampling of French materials in the library collection.

Saturday, May 8, 2010

VIVE LA FRANCE! LONG LIVE FRANCE!

Friday, February 19, 2010

AFTER HOURS VISIT BY FIU HISTORICAL METHODS CLASS

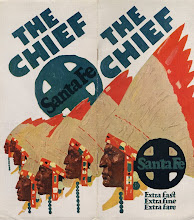

Last evening, Dr. Aurora G. Morcillo brought the graduate students in her Historical Methods class to our rare books and special collections library for a presentation by Mellon grant coordinator Jon Mogul and yours truly. The aim was to expose the students to some of the nonliterary primary source materials in our library and to help them learn how to “read” and make sense of the visual imagery and physicality of the artifacts. It is hoped that after their visit the students might began thinking about utilizing such materials not merely as illustrations, but as evidence as compelling and potentially revealing as anything offered in some of the more traditional literary sources. The library table in our main reading room was laid out in advance of their arrival with an array of diverse materials covering five areas of strength from our collection: World’s Fair catalogs and ephemera; a wide variety of items documenting various colonial projects of the late nineteenth and twentieth century; all manner of propaganda produced in the Soviet Union; Spanish Civil War leaflets and vintage postcards; and a variety of rare books, calendars, and portfolios illustrated by American Socialist and Communist artists in the 1930s.

Starting with the VTS (Visual Thinking Strategies) methodology, the students were asked to look at and describe exactly what they saw in the artifacts until the group collectively exhausted the imagery of the items. In order to interpret and make sense of the objects, the students were next asked to think about these same designed objects in the historical, social, and cultural context of the times in which they were made. They were encouraged to think about who produced the work and for what intent? Who was the intended audience? Was there a subtext or subliminal message buried in the text or image that the historical audience might have immediately or subconsciously recognized? How was the message meant to be distributed? Was there some relationship between the design of the object (photograph, photomontage, linocut, illustration, and caricature), its form (exhibition catalog, postcard, leaflet, and handbill) and the ideology its creators espoused?

I have included one item from each of the five categories mentioned above so that my readers might also have a chance to try their hand at parsing and interpreting the items for themselves. Feel free to comment with your own impressions and interpretations of these historical artifacts.

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

ALL THE WORLD’S A FAIR!

This past Monday, Dr. Lara Kriegel and eleven FIU students enrolled in her senior seminar: World’s Fairs, Exhibitions, and History, came up to our rare books and special collections library to meet the librarians and learn how to access the collection via our web catalog and how to schedule research appointments. Following the brief orientation, the students were treated to a presentation of original international exhibition materials aimed at giving them a chronological overview of the world’s fairs while simultaneously introducing them to themes that might serve to inspire their final research paper topics.

World’s fairs organized during the worldwide depression were often courted by cities anxious to provide work for the idle and unemployed, to stimulate tourism, and to provide at least some temporary boost to the economic doldrums. The corporate presence and pavilions at these later fairs often rivaled those sponsored and built by many smaller nations and reflect their growing influence in modern society, economy, and life.

Saturday, January 9, 2010

WOLFSONIAN LIBRARIAN NICOLAE HARSANYI DELIVERS TWO PAPERS

The second paper presented was “Programmatic Discourse and Problematic Realities” and focused on the rhetoric and legacy of the Proclamation of Timisoara (Romania) issued in March 1990. The latter presentation required little in the way of reading from his presentation paper as Dr. Harsanyi was able to rely on his own personal memories as a founding member of the society which issued the Proclamation, on the political and societal urgencies that engendered this document, as well as on the textual structure of it.

Both panels were attended by approximately fifteen scholars hailing from various universities across the United States.

Thursday, October 15, 2009

WOLFSONIAN FELLOW STUDIES 19TH CENTURY INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

The Wolfsonian library’s rich collection of original catalogs, guidebooks, official reports, and ephemeral items published by and for these international exhibitions is keeping him busy during the last two remaining weeks of his research visit. According to our scholar, “Every day brings new discoveries and greater familiarity with these events that attracted millions of visitors (and generated reams of printed paper!)" He adds that "It's interesting to read the jurors' reports along with the comments of critics and observers who wrote about the world's fairs - there's such a variety of viewpoints, praising the highest levels of skill, marveling at the technology which assisted the worker, while at the same time lamenting the absence of 'ordinary' furniture that the majority of visitors might actually buy and enjoy. Reconciling these often conflicting attitudes seemed to have occupied many observers at the time and contributes to our understanding of the history of design in the later 19th century."